Research Highlights

Sometimes, academic publications are not the best way to communicate research. That's why this section summarizes some of my publications, in a (hopefully) more accessible way.

Narcissists' Experience of Ostracism

Narcissism is associated with a sense of entitlement and self-centeredness, but different subtypes can be distinguished, with grandiose and vulnerable narcissists being the most prominent in previous research. Our research focused on grandiose narcissists, who exhibit entitled, self-centered, arrogant, dominant, manipulative, and self-enhancing behavior.

A growing body of research suggests that grandiose narcissists respond differently when ostracized. For example, they exhibit higher neurological reactivity after ostracism without necessarily reporting a greater threat to psychological needs than others typically do. Additionally, individuals with higher levels of grandiose narcissism display stronger retaliatory aggression toward both the sources of ostracism and uninvolved others.

Furthermore, ostracism is a subjective experience based on perceived social cues. This can lead to false perceptions of ostracism, where individuals may either be intentionally ostracized or merely believe they have been excluded without actual exclusion. Narcissists monitor their surroundings closely with heightened vigilance and may be especially sensitive to exclusion cues, perceiving social interactions as negative.

While grandiose narcissists may perceive ostracism more frequently due to the previous reasons, they may also experience actual ostracism more often because their particularly disruptive and norm-violating behavior poses a threat to group cohesion. Ostracism serves as a strategic tool to protect a group from individuals who fail to contribute or even harm the group.

Narcissism may not only increase the likelihood of experiencing ostracism but also be shaped by it, suggesting a bidirectional causal relationship.

We conducted two nationally representative panel surveys, an experience sampling study, and six experiments to examine the relationship between grandiose narcissism and ostracism. Our results show a strong link between narcissism and more frequent reports of ostracism, as well as greater sensitivity to ambiguous but not unambiguous exclusion cues. Furthermore, we found that narcissistic individuals are more frequently excluded due to their narcissistic traits. Lastly, a longitudinal study over 14 years revealed that narcissism is both a predictor and a consequence of frequent exclusion. Deviations in ostracism were followed by changes in narcissism one year later, and vice versa. Our findings demonstrate how negative perceptions, target behavior, and reciprocal causality together determine who gets ostracized.

Read the full article here.

Cultural differences in perceiving co-present phone use as phubbing: Evidence from six countries

Phubbing is the act of snubbing someone in a social setting by concentrating on one's phone instead of talking to the person directly. For exclusion to trigger negative emotional consequences, it must first be perceived as such. For instance, if a norm suggests that being left out is socially acceptable, being excluded hurts less. Importantly, the normative expectations of social interactions, how social situations are perceived, and what behaviors are considered appropriate are learned culturally. As such, culture may impact the subjective construal of co-present phone use as phubbing. Thus, phubbing appears to be a cross-cultural phenomenon. However, culture, especially the degree to which individuals self-define as a function of their social relationships (i.e., individualism-collectivism), may influence whether co-present phone use is perceived as disruptive.

Limited evidence exists on how different cultures perceive co-present phone use as phubbing. We test competing hypotheses regarding the effect of culture (i.e., individualism-collectivism) on perceiving co-present phone use as phubbing:

(1) Participants living in more individualist (versus more collectivist countries) report stronger perceptions of co-present phone use as phubbing.

(2) Participants living in more collectivist (versus more individualist countries) report stronger perceptions of co-present phone use as phubbing.

Cultural differences in the attribution of others' phone use may stem from rejection sensitivity, which tends to be higher in more collectivist cultures. Individuals in collectivist cultures may also be more likely to attribute others' phone use to external factors.

Based on these considerations, we examine whether the attribution locus (i.e., internal versus external) of situations involving co-present phone use differs based on culture. We also explore whether attribution locus mediates the relationship between culture and phubbing perception.

Each participant was presented with 25 vignettes describing co-present phone use. Some depicted situations most people would not consider phubbing, while others illustrated situations most people would. Participants were instructed to imagine each of these social interactions involving phones. The vignettes successfully produced a range of phubbing perception scores, from very low to high.

The study found no significant cultural effect on phubbing perception, though individuals from collectivist cultures tend to perceive phubbing more than those from individualist cultures. However, culture significantly influences attribution locus, with collectivists more likely to internalize blame for phubbing. Attribution locus mediates the cultural effect on phubbing perception, highlighting the role of cultural context in interpreting co-present phone use. These findings provide a foundation for future research on the cultural dynamics of phubbing.

Read the full article here.

"This Message was Deleted": The Psychological Consequences of Being Out of the Loop During Messenger Use

Most people have encountered delete notifications in messenger apps. While subtle, these notifications can have negative psychological effects, making recipients feel confused, hurt, or left out of the loop. This study examined whether receiving delete notifications also represents an exclusion experience.

We hypothesized that:

(H1) Being excluded—whether through ignored messages (ostracism) or deleted messages (out-of-the-loop)—lowers mood and threatens users' belonging, self-esteem, meaningful existence, and control compared to social inclusion.

(H2) Ignored messages (ostracism) are expected to have a stronger negative impact on mood, belonging, self-esteem, meaningful existence, and control than deleted messages (out-of-the-loop).

(RQ1) Does fear of missing out (FoMO) influence how ignored messages affect mood, belonging, self-esteem, meaningful existence, and control?

(H3) Users with higher FoMO should experience stronger negative effects from deleted messages on mood, belonging, self-esteem, meaningful existence, and control.

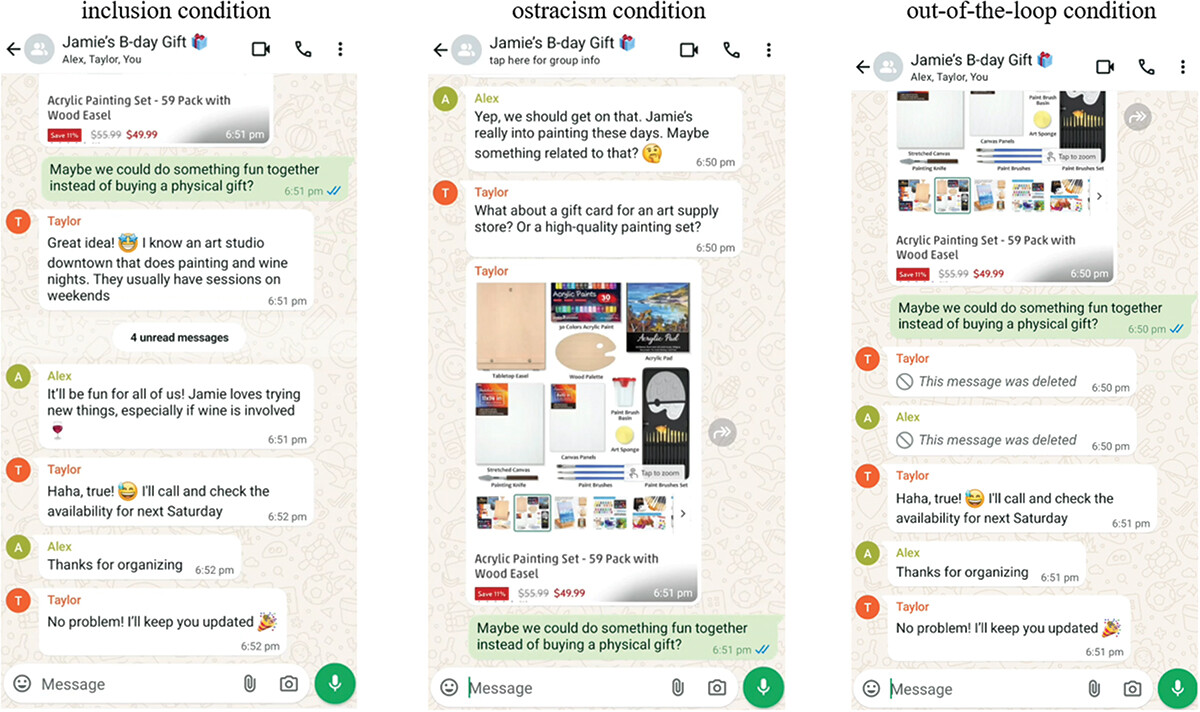

To test these hypotheses the participants watched screen recordings of a WhatsApp group chat. They were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: (1) Inclusion (they received responses and participated in the conversation), (2) Ostracism (their message was ignored), or (3) Out-of-the-loop (a message was deleted before they could see it but the content was relevant to the ongoing conversation).

The results showed that both ostracism (being ignored) and out-of-the-loop experiences (seeing deleted messages) had similar negative effects. Compared to inclusion, both conditions led to a worse mood and threatened needs for belonging, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. However, only ostracism significantly threatened users' sense of control. Surprisingly, FoMO did not amplify these effects, meaning all users felt similarly excluded. These findings suggest that deleting messages can make recipients feel just as excluded as being ignored, highlighting the need for more user-friendly communication features.

Read the full article here.

The Pursuit of Approval: Social Media Users' Decreased Posting Latency Following Online Exclusion as a Form of Acknowledgment-Seeking Behavior

Social media shapes social interactions and has become an integral part of human life. While it simplifies communication, it also introduces new forms of negative experiences, such as social exclusion when a post does not receive enough likes or engagement. The lack of attention, or social isolation, is more emotionally distressing than bullying or rejection, as it represents being rendered invisible or meaningless.

To cope with social exclusion and recover needs for acknowledgment and control, people may seek reconnection, act aggressively, or withdraw from social interactions. Social media offers unique ways to cope, such as posting new content or engaging with others' posts.

In these studies, we analyzed observational data from Twitter (now "X") and Reddit to explore how users behave after experiencing social exclusion. We hypothesized that:

(1) Users may behave to reconnect with many others

(2) Users may behave to reconnect with specific individuals

(3) Users may withdraw from the situation

To measure this, we analyzed users' online behaviors following social exclusion, defined by a lack of popularity of users' posts compared with their usual popularity. We focused on the duration until the next post or comment after an unpopular post. Shorter time until another post indicated attempts to reconnect with many other users. Shorter time until a user's next mention, retweet or comment indicated attempts to reconnect with specific individuals. Longer time until a user's next post, mentioning or retweet indicated withdrawal from social media.

When social media users experience an unpopular post, they tend to post again more quickly to a broad audience. This behavior aligns with the idea that people seek acknowledgment rather than likes after feeling excluded online, as they aim to reconnect with many people and restore a sense of belonging. The effect is most noticeable after particularly unpopular posts compared to average ones, suggesting the response is tied to exclusion rather than general posting habits. However, users are less likely to target specific individuals after feeling excluded, possibly due to the higher risk of being ignored. The results of our studies therefore support our first, but not the second and third hypotheses.

Due to our study design, the effectiveness of posting again quickly after exclusion on social media for recovering threatened needs remain unclear.

Read the full article here.

Ostracism in Everyday Life: A Framework of Threat and Behavioral Responses in Real Life

Ostracism can lead to various behavioral responses in its targets. In this publication, we propose and test a framework to explain this range of behavioral reactions. Specifically, we suggest that the more strongly psychological needs are threatened after being ostracized, the more likely individuals are to exhibit antisocial behavior or withdrawal. Conversely, if the threat is less intense, the response may be more approach-oriented.

We explored the following questions:

(1) How frequent is everyday ostracism, and who engages in ostracism in different contexts?

(2) Does ostracism threaten psychological needs in everyday life?

(3) How do individuals behave after being ostracized in real life?

(4) How is the threat to fundamental needs related to behavior following ostracism?

When asked to report experiences of ostracism, people tend to recall intense instances and overlook smaller ones. This recall bias results in an overrepresentation of highly unfair and painful experiences in the data. To address this, we used an event-contingent experience sampling method in the first study, where participants report ostracism as it occurs. In the second study, we employed a time-contingent approach, asking participants to report any ostracism experiences they had within the past hour on five occasions throughout the day.

Our findings showed that ostracism occurs across a variety of contexts and relationships, with an average frequency of 2-3 times per week, and is typically accompanied by a significant threat to psychological needs. As outlined in our framework on need threat and behavioral responses to real-life ostracism, we observed that the greater the threat to individuals' needs, the more likely they were to respond with avoidance or antisocial behavior rather than approach behavior.

Ostracism was reported in nearly 10% of all situations in Study 2, indicating that approximately 1 in 10 daily life situations involves ostracism— a higher rate than other negative interpersonal experiences. Interestingly, a small proportion of participants accounted for almost half of all reported ostracism experiences in both studies (14% in Study 1 and 10% in Study 2). This suggests substantial individual differences, which warrant further investigation into risk factors for frequent ostracism in future research.

Read the full article here (green open access).

Ostracism experiences are associated with more frequent doctor visits over time

It is well established that being excluded and ignored, ostracism has a significant negative impact on individuals' health. In this study, we examined the relationship between the frequency of feeling ostracized and the utilization of the healthcare system.

We hypothesized that:

(1) Ostracism may contribute to the development of illnesses.

(2) Using healthcare services may serve as a coping mechanism after experiencing ostracism.

(3) Individuals who use healthcare services more frequently may be more likely to experience ostracism as a form of health stigmatization.

We analyzed two waves from the Innovation Subsample of the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP-IS), a longitudinal, representative study of private households.

Our findings showed that ostracism predicts more frequent doctor visits three years later. However, we found no evidence that higher ostracism frequency leads to an increased number of medical diagnoses. This suggests that the use of healthcare services as a coping mechanism is a more plausible explanation for the observed effects than the development of illness caused by the stress of ostracism. Visiting doctors as a way of coping may help alleviate the psychological need threats caused by ostracism, such as diminished belonging, control, and self-esteem.

Additionally, we found that the number of medical diagnoses predicted reports of ostracism three years later, but the frequency of doctor visits did not. The dissociation between medical diagnoses and doctor visits in predicting future ostracism experiences could have several explanations. Frequent doctor visits might signal a greater commitment to maintaining health, whereas medical diagnoses rarely indicate overall well-being.

Not all coping strategies for dealing with ostracism are beneficial in the long term. While frequent doctor visits are certainly less harmful than turning to drugs, they may not be helpful unless physicians correctly identify ostracism as the underlying cause of a patient's visits. Doing so could prevent patients from receiving unnecessary physical treatments or medications and, as a result, reduce costs for the healthcare system.

Read the full article here.

Ostracism Experiences of Sexual Minorities: Investigating Targets' Experiences and Perceptions by Others

People who identify as lesbin, gay or bisexual face frequent discrimination, maltreatment and violence. The role of ostracism, being excluded and ignored by others, is an understudied form of discrimination against lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals (from here-on: LGB).

In three studies we investigated two questions:

(1) Do LGB people feel ostracized more often than straight people?

(2) Are LGB people who don't fit traditional gender roles or are perceived to have a different sexual orientation more likely to be ostracized?

We used surveys from the representative German Socio-Economic Panel (Innovation Subsample, SOEP-IS 2015, 2018, and 2022), real-time reporting via smartphones, and a rating experiment to gather data to address these questions. The results suggest that LGB individuals face more ostracism compared to straight individuals: They reported more frequent ostracism experiences in retrospective surveys and during real-time data collection. In addition, perceptions of who is likely to be excluded were influenced by gender: Lesbians were seen as the most likely group to be ostracized. Additionally, breaking traditional gender roles was the strongest reason others believed someone would be ostracized.

Overall, our findings highlight the ongoing social challenges faced by LGB individuals, who experience exclusion more frequently in their daily lives compared to their heterosexual counterparts.

Read the full article here.

The power of human touch: Physical contact improves performance in basketball free throws

This study examined how teammates' physical touch affects performance in stressful situations, specifically free throw shooting in women's college basketball.

When a player is fouled, they often get two free throws, each worth one point. Not seldomly, free throws decide the outcome of games. We analyzed recordings of 60 games, covering 835 free throw attempts. Results showed that if a player misses the first shot, a touch from a teammate increases the chances of making the second shot, regardless of the player's skill level or game circumstances. While this touch doesn't directly lead to winning individual games, it contributes to better season performance, likely due to stronger team support.

Interestingly, zero, one, three, or four touches had a greater impact than the receiving two touches, which seems to be the default. This aligns with research that unusual behaviors carry more important information: Receiving more than two taps might show extra effort from teammates because the two teammates who are not positioned in the rebounding position close to the free throw shooter must actively approach the player to touch them, while a lack of touch from nearby players could be seen negatively.

The study focused on female college basketball players, a group often overlooked in research. Previous research shows no significant differences in pressure performance between men and women, therefore the observed effects likely applies to male athletes as well.

Read the full article here.

Young, unemployed, excluded: Unemployed young adults experience more ostracism

Finding a job can be tough, and the social impact of unemployment is often overlooked. Unemployed people, especially young adults, are often unfairly seen as lazy or unmotivated, which can lead to social exclusion and negative interactions.

In three studies, we investigated whether

(1) unemployed compared to employed individuals report being ostracized more frequently and whether they feel more like outsiders

(2) younger compared to older unemployed individuals report ostracism more frequently and feel more like outsiders.

Three studies with participants from Germany, New Zealand, and the UK show that unemployed individuals, particularly younger ones, report feeling ostracized and like outsiders more frequently than employed people.

The negative effects of social exclusion may involve increased frustration and self-doubt, creating a challenging cycle. To address this, support programs should offer not just job training but also career counseling and mentorship to help unemployed people regain their sense of purpose and structure.

Communities can play a key role by helping unemployed individuals set work-related goals and connect with others in similar situations. Creating supportive environments, like networking events, can improve their chances of finding employment and feeling included.

Ultimately, fostering an inclusive society is crucial. By supporting unemployed young adults and acknowledging their challenges, we can help break the cycle of exclusion and ensure everyone has a fair chance to succeed.

Read here a blog post about this article by lead author Elianne Albath.

Read the full article here.

When and why we ostracize others: Motivated social exclusion in group contexts.

Can you think of an occurrence where you and your group of friends decided not to pay attention to an aggressive, loud stranger accosting you? Or chose not to invite a person to participate in a project group, knowing that the person lacked the skill and experience of the other group members and would have inevitably slowed the group down? On average, people report one or two instances per day in which they either experienced ostracism themselves or ostracized another person. Not all of them can be explained with malicious intent or undifferentiated dislike of the target by ostracizers, as commonly assumed.

In seven studies we explore why people ostracize others, based on how valuable a target is perceived as a partner. We identified two key reasons for ostracism: perceived norm violations, when someone breaks social rules, and perceived expendability, when someone is seen as unnecessary or not useful.

Our results showed that people are more likely to ostracize others who have broken norms or are seen as expendable. Furthermore, the context matters. People with social or performance issues were generally more likely to be ostracized, even if those issues weren't relevant to the task at hand. However, in cooperative settings, norm violators were more likely to be ostracized, while in performance-oriented settings, those lacking task-relevant skills were more likely to be ostracized.

This suggests that ostracism is a way for groups to maintain effectiveness by excluding members who don't meet the group's specific needs at the time.

Read the full article here.

Showing with whom I belong: The desire to belong publicly on social media.

Do you enjoy posting pictures of you and your friends on Instagram, Facebook, or TikTok and tagging them? Is it important to you that people who visit your profile see you spending time doing great things with your friends? If so, you might have a higher level of DTBP, or desire to belong publicly.

We all have a fundamental need to belong. When this need is not met, it can negatively impact our well-being. In today's world, social media is a big part of our daily lives, extending our social interactions into the digital realm. We wanted to understand how and why people use social media and how it affects their sense of belonging.

We assumed that posting on social media not only fulfils belongingness goals but also allows people to display their real-world connections to a broader audience, intensify the positive psychological effects of belonging.

To measure this desire to belong publicly, we developed an eight-item scale. This scale captures the desire to showcase both the quantity (having many friends) and the quality (having close friends) of friendships on social media. With the concept of DTBP gives us the possibility to bridge the gap between real life and social media.

If you are curious about your level of DTBP, you can find our scale below.

Read the full article here.

Your phone ruins our lunch: Attitudes, norms, and valuing the interaction predict phone use and phubbing in dyadic social interactions

Phubbing describes the phenomenon of ignoring another person while using a smartphone in the present situation. It is an increasingly common behavior that can have negative consequences for one's social interactions, relationships and work performance. People who are phubbed feel annoyed and ignored, which can harm relationships and mental health.

In this study we wanted to learn more about this phenomenon. Why do people phub even though it may hurt their relationships? To answer that, we asked Students leaving the university cafeteria in pairs to answer a few questions about the lunch they just shared.

We found that people's attitudes toward phubbing were the strongest predictor of phubbing behavior. Interestingly, while subjective norms (beliefs about what others think is acceptable) did not predict phubbing, they did predict phone use when with others. Valuing social interactions didn't predict phubbing but did reduce overall phone use, suggesting that people may use their phones less during important conversations.

We also differentiated phubbing from other phone-use behaviors, such as screen-sharing. Positive attitudes toward phubbing were linked to both general phone use and phone use in the presence of others (co-present phone use). Subjective norms only correlated with co-present phone use.

An interesting finding was that the person who started phubbing tended to phub more, suggesting that phone use might be contagious in social settings. This could lead to a cycle of increased phone use and a decreased interaction value.

Read the full article here.

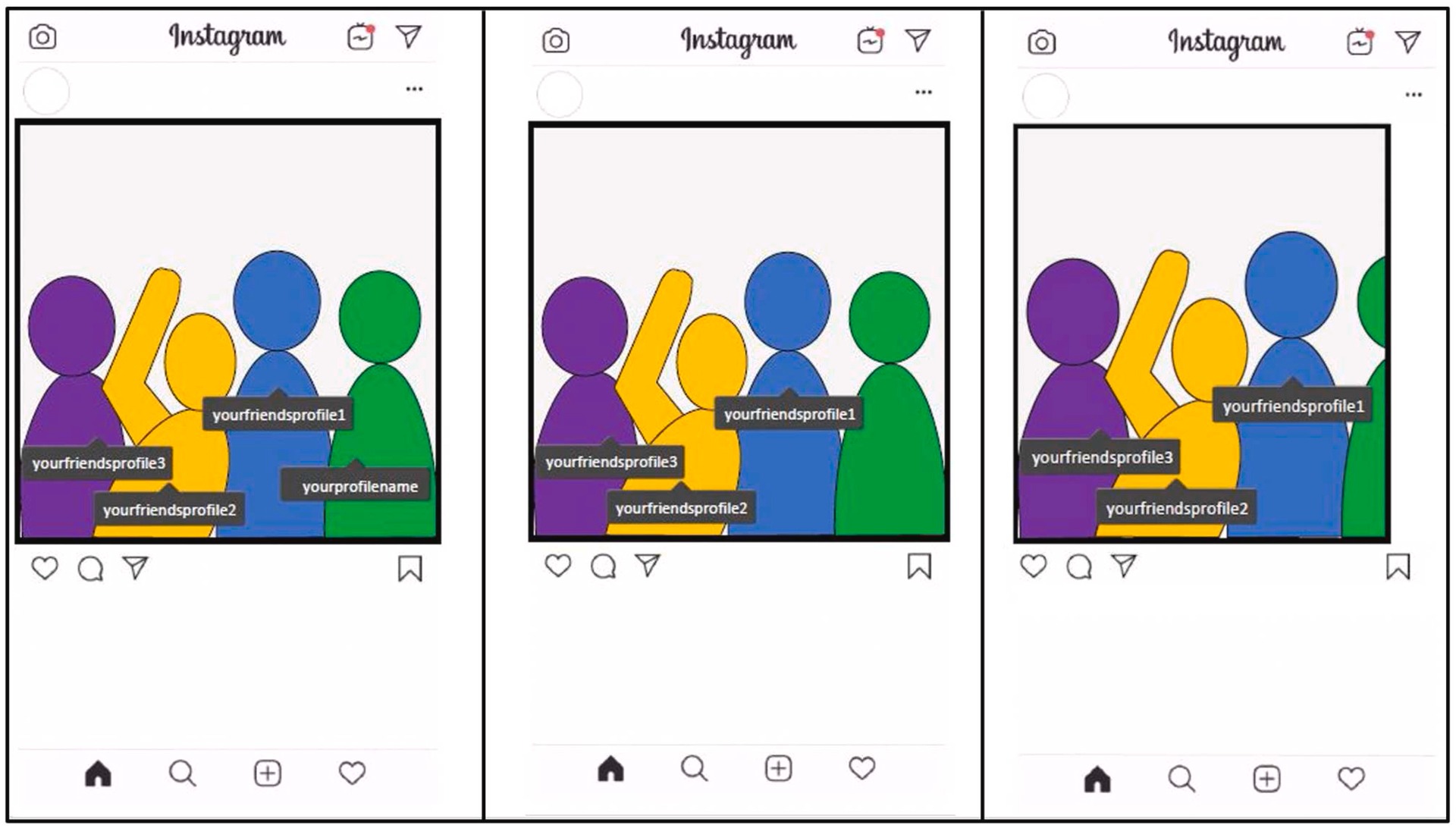

Why didn't you tag me?!: Social exclusion from Instagram posts hurts, especially those with a high need to belong

Social exclusion on social media can take various forms, for example, being unfriended, left on read or not receiving the usual number of reactions to a post. Not being tagged in someone else's post is another possible way to experience ostracism on social media, which is the type of exclusion we focused on in the five studies of this project.

In one study we asked around 300 people to imagine how they would react to these scenarios:

(1) being tagged in a posted group photo,

(2) being in a posted group photo but not tagged, though everyone else is, and

(3) being cut out of the posted group photo altogether.

Our results show that individual differences play a key role in how this form of exclusion affects people: On one hand, those with a high need to belong felt more threatened and reacted more negatively compared to people with a lower need to belong. But on the other hand, being cut out of a photo is such a painful experience, that those individual differences no longer matter.

People should keep in mind that their interactions with one another online could potentially have real-life consequences when they go online. Feeling left out in the "digital realm" may be just as damaging as feeling left out in the workplace, in the classroom, or with friends.

Read the full article here.